Cross-Cultural Australian Perspectives on the Pandemic

Port Jackson Figs in Sidney Harbour. Photo by Phil Hunt.

By Phil Hunt and Liesa Clague

When the coronavirus was officially declared a pandemic, many remote Aboriginal communities in Australia had already been closed to outsiders. Aboriginal organizations such as the national health body, National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation, had advised Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders to close their areas to outsiders and asked families and communities to self-isolate. Despite such early precautions, members of these groups across the country would soon be putting themselves at risk in some of the largest black protests Australia has seen. How could the death of George Floyd on the other side of the world lead to such high-risk actions? The answer so often leads back to what Australia knows, or does not know, about itself.

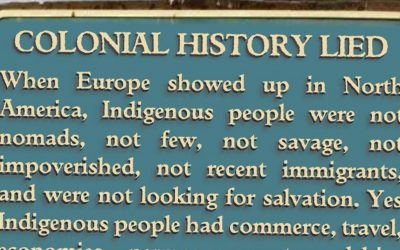

As the pandemic was declared and people sought comparable examples throughout history, many people overlooked what is habitually overlooked in Australia: “The Aboriginal story.” The first recorded pandemic was not the Spanish Flu that shut down the young nation in 1918. It was smallpox in 1789. It devastated the enduring Aboriginal clans around the Sydney basin and even further afield. Its effects are still being felt, with Sydney communities trying to regroup 230 years after the setting up of the penal colony by the invading British, who took possession of land and water and destroyed many of the tribal groups and their rich culture based around an ecological lifestyle. With forced assimilation to an alien society and with the antipathy and indifference of the descendants and benefactors of the invading peoples evident even today, the challenges have been enormous.

The #blacklivesmatter protests have given Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples an opportunity to highlight injustices here in Australia. Just as most Australians are not aware of the first pandemic that predominantly affected Aboriginal people, they are ignorant about the deaths in custody and slavery in their own backyards. Some of the incidents are frighteningly similar, with the last words of David Dungay in 2015 also being “I can’t breathe.”

The lived experiences and cultural lens through which we look and interpret the world around us is different. However, there are some things that can be understood universally. Firstly, we are not alone. Secondly, the world is in trouble because of human actions and it needs improved human actions to achieve outcomes that are healthy for all.

When protests across the country were organized, many Australians were shocked and angry at the events that were unfolding during a pandemic. However, as debate spread and facts were revealed, a different kind of shock arose as people found out about how many black deaths have occurred in police custody — there have been 437 since a royal commission report into the issue in 1991. People became embarrassed to learn they were outraged at something happening in another country but did not know it was happening in their own. While commenting on the protests our own Prime Minister, Scott Morrison, reiterated a common myth most Australians believed when he declared there had been no slavery here. When asked about ‘blackbirding’ (the capture of islanders from the Pacific to be forcibly used as labourers in Australia) he had not heard of the term. This is why Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander representatives have been so motivated to raise concerns and alarm in the media. It is a time when the message can finally come out and be acknowledged as truth.

However, we must not fall into the trap of generalizing by being aware that not everyone could or wanted to protest. Many people remained at home. Like Canada, Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities have significant health issues relating to poverty and being marginalized, which puts them at higher risk of COVID-19. These communities also do not have the medical facilities that can deal with a crisis like COVID-19.

Australia is a large country with hundreds of different Aboriginal nations — each with rich cultures and stories. Every tribe and clan has its own history and current reality. Yet too often our diversity as tribal groups is thrown together as one. Suffering can be generalized, however, every community and every individual experiences their own specific pain and struggle.

When you are proud of your country, anything that tarnishes that image causes anguish. The nation is part of everyone’s identity. When Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples raise their voices together, Australia as a nation needs to reflect and listen to what is being spoken, even though there will be a point where the faults in the nation’s history are highlighted. Our history is directly related to the current day, and we need to learn from previous actions and reactions by government, organizations such as churches, educational institutions, the police and health systems, that continue to marginalize Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Many Australians do not see themselves as racist, but we follow a discriminatory methodology when looking at the diverse ways Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander stories unfold. It is not just one people, one story, one problem, one solution. Many Australians are not aware of, or lack understanding of the cultural significance of Aboriginal people declaring that they are Anangu or Wiradjuri or Yaegl first, rather than Australian.

At a time when it is most important for everyone to work together, the lack of understanding about Australia’s ‘black history’ has reignited the divisions between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people. However, one of the most important lessons we keep needing to relearn is that nothing is black and white. This is seen in nature — it shows us time and time again. For many who have had a chance to return to Country, (the place where you and your ancestors are from) breathing in the familiar smells and reconnecting to the land by listening to nature and its messages has reinforced the importance of caring for Country and ourselves with a holistic approach.

The authors of this paper have different backgrounds and experiences. The lived experiences and cultural lens through which we look and interpret the world around us is different. However, there are some things that can be understood universally. Firstly, we are not alone. Secondly, the world is in trouble because of human actions and it needs improved human actions to achieve outcomes that are healthy for all. It requires sincere responsibility and commitment. For Aboriginal peoples, being on Country helps them realize the wealth and healing nature of the environment, its need for recovery and the necessity of not viewing the world solely on our own prejudices. We need to acknowledge the interconnections, how impacts in one place can have a rippling effect that joins us all to the events that unfold around us, within us and from our emotional, spiritual and physical connections and surroundings.

We must work out ways to show humanity how to work together, think logically and support sustainable ways of meeting the needs of groups of populations affected and effected by isolation, poverty and trauma that is happening worldwide. Perhaps the first step is looking honestly at our shared history and acknowledging what has occurred truthfully, as the lived experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. In many respects Indigenous peoples around the world in all their diversity have been facing crises more often than their non-Indigenous neighbours. They also have thousands of years of experience in problem solving at the local level and more broadly. They have had to collaborate with other tribal groups when significant events occur in a manner that also aims to enhance the natural world. This is the time to look closer at this wisdom and see how these long-cherished traditions and values can help us move forward positively for the future generations and the environment.

Dr. Liesa Clague is an Aboriginal woman of the Yaegl, Bundjalung and Gumbaynggirr peoples of the North Coast New South Wales on her mother’s side, and Celtic Manx heritage from the Isle of Man on her father’s side. Liesa acknowledges her nursing and midwifery profession and the health sector experiences that she has worked in. Liesa has 27 years of experience of networking with different teaching organizations and health professionals. She feels that there is a need to create an environment of connection to the skills and problem-solving activities to achieve more positive outcomes for the community. Her knowledge lies in qualitative data analysis. Liesa uses the perspective of an Aboriginal philosophical approach called Gan’na a Bundjalung, a word which means hear, think, feel and understand.

Phil Hunt is a senior archaeologist with the Aboriginal Heritage Office in Sydney. He has been involved with heritage conservation for many years, from mapping areas of cultural heritage in Peru and Russia to surveying endangered snow leopards in Mongolia, as well as Aboriginal heritage projects in many regions of Australia. He is co-founder of the Australian charity Tree of Compassion and helps a number of charities involved in humanitarian, environmental and animal care and rescue.