Community Archaeology: Handing Back the Power of the Past

The community of Quinhagak, Alaska, where the Nunalleq Project is inspiring Yup’ik youth about their history and culture. Photo by Sean O’Rourke.

By Sean O’Rourke

It’s July 2015 and, after leaving Canada some 40 hours prior, I find myself on a tiny plane descending rapidly into Quinhagak, Alaska, an out-of-the-way Yup’ik village roughly 745 people call home. As the 10-seater Cessna cuts through haze blown in from forest fires hundreds of kilometres away, the tundra’s intricate beauty comes into focus: This treeless-but-lush landscape is endlessly dissected by an ever-changing network of meandering streams lazily draining into the Yukon and Kuskokwim rivers before rushing toward the Bering Sea.

Tundra outside Quinhagak, Alaska. Photo by Sean O’Rourke.

I soon learn, however, that the river-scape is not the only thing shifting in the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta, a region twice the size of Scotland (and just as rainy). As a fledgling archaeologist, I’m flying to Quinhagak to partake in a field school at the Nunalleq Project—one of a few recent excavations turning the discipline of archaeology’s typical power structures on its head.

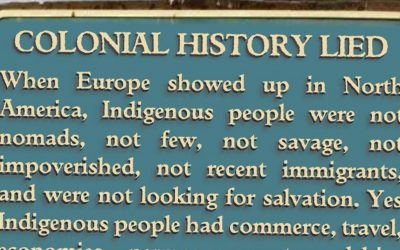

Power and Archaeology in the “New World”

Power relations shape archaeology as they do nearly every other human context. In North American archaeology, the balance of power has historically favoured archaeologists, giving the Indigenous cultures they study little say regarding the fate of their material heritage or whether it is dug up in the first place. Early archaeology in the so-called “New World” often amounted to little more than treasure hunting.

In 1838, a pair of brothers gutted the Grave Creek Mound in West Virginia, the largest conical burial mound on the continent. The siblings transformed it into a museum (and later a saloon and dance floor), selling artifacts and human remains they encountered—many of which, like the valuable scientific data the mound once held, were never recovered.

Though during the 20th century archaeology evolved into the systematic and regulated discipline we know today, Indigenous perspectives mostly lingered out of sight. Communities felt powerless as they watched their cultural heritage excavated and shipped around the world. At the dawn of the 21st century, nearly 20,000 Native American artifacts were in British museums. Over the past few decades, however, the discipline has slowly been shifting toward an equilibrium and a reality of genuine, equitable partnership has begun to emerge. Today, Indigenous groups hold more decision-making clout in archaeology than ever before—a tool some, like Quinhagak, now wield to empower their communities.

The Nunalleq Project: New Ideas from the Old Village

My plane touches down on Quinhagak’s bumpy gravel airstrip and I shyly hitch a ride with a gruff postal worker to meet my team at the community centre (or “the big red building,” as the packages I sit beside call it). I shuffle in the door and Charlotta Hillerdal, one of the head archaeologists, begins briefing our crew on what we’ll be doing over the next month. She explains how the Nunalleq (“old village” in Yup’ik) Project is the excavation of a 600-year-old Yup’ik village perched precariously on the rapidly eroding Bering Sea coastline and that our job is to excavate, document and preserve as much of it as possible before it is lost to the region’s notoriously vicious winter storms. Due to climate change, the ground does not freeze here like it used to, and more and more of the coast washes away each year. Hillerdal emphasizes that the excavation is jointly directed by the University of Aberdeen and Qanirtuuq Inc., the village’s corporation, so we should all expect to meet and work with locals. Being my first archaeological experience, this does not strike me as noteworthy—but I could not have been more wrong.

The author working at Nunalleq in July 2015. Photo by Lindsay Paskulin.

On our first day at Nunalleq, the rain never stops. Covered head to toe in mud, I wonder what I signed myself up for. But on the second day, the sun comes out—and so does the community. All day long, whole families—elders, parents, children, even family dogs—cram onto their ATVs and drive down the sandy beach from Quinhagak to visit. Though elders and parents mostly chat with the archaeologists as they walk around the excavation’s edges, peering down over our shoulders, the kids and teens almost always get down in the mud and dig with us. My colleagues and I teach them to identify common artifacts (like stone flakes or wooden dolls and darts), trowel with care and screen dirt. Judging by the smiles and laughter that fill our camp, they love it. Whenever we host open houses, Yupiit of all ages clamour to catch a glimpse of our most recent discoveries. In addition to the hundreds of immaculately preserved museum-quality artifacts we regularly unearth—a human-walrus transformation mask, tattoo needles, an amber necklace and intricate ivory earrings, to name a few—we excavate hundreds upon hundreds of razor-sharp stone arrowheads. “It was like a drive-by shooting,” co-head archaeologist Rick Knecht says.

All day long, whole families—elders, parents, children, even family dogs—cram onto their ATVs and drive down the sandy beach from Quinhagak to visit.”

In fact, it is because of interested locals that Nunalleq got started in the first place. In the mid-2000s, beachcombing villagers began noticing artifacts washing up with the tide. Qanirtuuq Inc. contacted Knecht, who was previously at the University of Alaska Fairbanks before moving to the University of Aberdeen, and in 2009 Nunalleq was discovered. It is unusual for a Yup’ik community to request the assistance of archaeologists—Yupiit tend to believe the past should stay in the ground—but they made an exception and chose to study Nunalleq rather than lose it forever. According to Hillerdal, “It sparked an engagement with Yup’ik traditional culture, especially among the younger generation.”

I spend much of July on hands and knees clearing tundra moss with my trowel and picking salmon vertebrae out of my screen. The villagers tell me that Nunalleq is transforming how youths see themselves and their culture, and I cannot get their words out of my head. Parents praise the education programs that blossom from Nunalleq, such as carving workshops facilitated by elders and a cultural art program that urges schoolchildren to explore what it means to be Yup’ik in the modern era. One local man I befriend, Mike Smith, got involved with Nunalleq as a teen distraught over a break-up. Working with the archaeologists encouraged him to take up Yup’ik carving. “This project saved me,” he would later tell the Anchorage Daily News.

Over a cup of tea, a teacher at the community school describes how Nunalleq both inspired youths to create dances about their ancestors—the first time Yup’ik dancing has occurred here since it was banished by missionaries over a century ago—and galvanized one of her students, Angela, to give a prize-winning speech on the importance of learning about the past. In her speech, Angela says, “The dig site has taught me the importance of staying in school so that I can be involved in this when I get older. I want to be able to share the artifacts with my family one day. I want to encourage everyone in my community to use the resources around them to learn about their culture. Through the dig site I have become more proud of who I am and where I have come from.”

My Research: How Does Nunalleq Affect Yup’ik Youth?

On a blustery, sunny day in September 2016, I again find myself on a plane traversing the tundra en route to Quinhagak. With Mike Smith as my research partner, I’m here to speak with elders, parents and educators about the effects Nunalleq is having on youth. Qanirtuuq CEO Warren Jones has said, “One of the big reasons for this project was to help our future generation get back to our history and culture, so all this work is basically for our children and the future generations.” Based on what Smith and I hear from community members, these efforts are paying off.

Mike Smith plucks a salmon out of the Bering Sea on the mud flats next to Nunalleq. Photo by Sean O’Rourke.

The school’s Yup’ik language teacher, Keri, explains how Nunalleq makes youth “appreciate their culture because they know what the weather can get like here. If our ancestors didn’t make it, then we wouldn’t be here.” This appreciation, according another teacher, Alicia, “makes them value who they are.” She links the Nunalleq-inspired resurgence of Yup’ik dancing to further psychological changes: “We have one kid I can think of in particular. He is the best native dancer. It has helped a lot of our kids feel confident. Those kinds of things help the kids realize they can be whatever they want. The Yup’ik dancing for sure has helped a lot of our kids. You see them up there dancing, and it’s like they’re shining.”

The Nunalleq Culture and Archaeology Centre: A Milestone in Community Archaeology

A decade of close collaboration between Qanirtuuq Inc. and the University of Aberdeen recently culminated in the Nunalleq Culture and Archaeology Centre, which opened last August. The museum ensures artifacts can be preserved right in the village. At over 70,000 pieces, it is now the largest collection of pre-contact Yup’ik artifacts in the world. Archaeological materials are typically whisked thousands of kilometers away to university laboratories for preservation, analysis and storage, but Quinhagak now has the power to decide what happens to their material heritage and share their past with generations to come.

“I almost broke down. It’s our culture. It’s priceless to us,” Qanirtuuq Inc. CEO Warren Jones said at the museum’s opening ceremony. “They will be here with us forever. When I’m gone, when we’re gone, they’ll be in the village. And future generations can come at any time and look at them, and never forget where they came from.”

Archaeology by the Community, for the Community

Since the 1970s, a movement toward Indigenous collaboration and community-based research has been picking up momentum in both professional and academic spheres. Community-based archaeology projects like Nunalleq prioritize community involvement and capacity building by training and incorporating locals, as well as sharing decision-making power with community leaders. Prominent archaeological organizations like the Canadian Archaeological Association urge collaboration, because it promotes socially responsible research and adds depth to the archaeological process. According to Hillerdal, community involvement is what makes archaeology relevant.

“Community engagement affects the way we do archaeology and also the questions that are asked to the material,” she says. “Involvement from the community and inclusion of local knowledge contributes to more complex interpretations and also a more ‘grounded’ archaeological practice.”

Her words underscore one of community-based archaeology’s central tenets—and greatest strengths: an equal reliance on Western scientific and Indigenous knowledge systems when interpreting the past. When community members participate in a dig, they bring life experiences, cultural knowledge and fresh perspectives that help researchers address puzzling questions and generate new hypotheses. When locals are involved, “archaeologists and community members learn from each other, and the result is a shared story,” Hillerdal says.

Sunset on Quinhagak’s Moravian church. Photo by Sean O’Rourke.

The metamorphosis of archaeology as a colonial discipline into one in which the studier and the studied stand on equal footing is not yet complete. Significant work remains to be done. Leadership roles in archaeology’s academic and professional sectors are sorely lacking Indigenous voices. Governmental regulations regarding Indigenous archaeology are incomprehensive and many artifacts remain tucked away in repositories, gridlocked by outdated policies. Some in the field of cultural resource management seem as reluctant as their cousins in natural resource industries to understand Indigenous issues. Nevertheless, a handful of community-oriented projects and the growing number of Indigenous students in archaeology indicate the discipline is headed in the right direction.

As time treads on, more archaeologists realize the power of material culture to profoundly reshape the realities of people alive today. The sooner society acknowledges that the past does not have to be cut off from the world by museum glass, the sooner we will be able to embrace and celebrate this aspect of our shared humanity. As a father with whom I spoke in Quinhagak put it, community-based research can provide the key to the past: “It’s up to us to unlock the door.”

Learn more about the Nunalleq Project and keep up to date on its recent developments by following the Nunalleq blog. Read more about my research by reading an article I recently published in The Journal of Archaeology and Education.

Sean O’Rourke is an interdisciplinary studies (psychology and geography) graduate student at the University of Northern British Columbia researching the intersection of meaning in life and land-use with Eveny reindeer herders in Siberia. Although he grew up in Calgary, Sean has lived in northern BC for the past two years. He has spent the past four years undertaking anthropological and psychological research in collaboration with Indigenous communities throughout the circumpolar north.