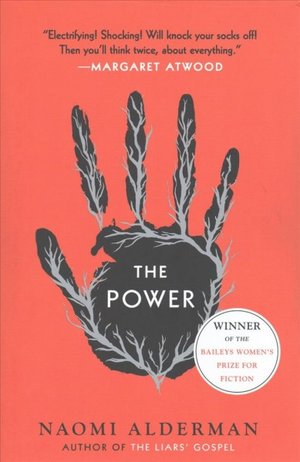

Naomi Alderman’s The Power (BOOK REVIEW)

Photo by Mervyn Chan/Unsplash

By Michelle Larstone

“Power tends to corrupt and absolute power corrupts absolutely.” ~ John Dalberg-Acton

What would the world be like if women were in charge?

What would the world be like if women were in charge?

This is a central question Naomi Alderman asks in her dystopian novel, The Power (Viking Press, 2016). All peace and love, right? Her answer was not what I expected.

The story unfolds as teenage girls begin to discover their bodies hold a deadly electrical power they can unleash from their hands. The power is stored in a “skein” under their collarbones and awakens when the girls turn 15. At first, the girls don’t know how to control it; it’s at once scary and exciting. Boys their age feel the same way as they witness their friends and girlfriends experiment with their power. Once the girls discover they can use their hands to awaken the dormant power in older women, the phenomenon spreads like a virus and the balance of power begins to shift.

Early in the book we are introduced to Allie, who uses her power to kill her abusive step-father and flee town. Roxy, the daughter of a powerful London mob boss, electrocutes her mother’s attacker. Margot is an ambitious politician who watches her teenage daughter struggle to control her power, and manages to capitalize on what is happening. And there’s Tunde, a Nigerian boy who fancies himself a photo journalist, who sees what is happening early and realizes it will change the world.

Alderman knits these characters together in a way that makes for a gripping read. She plays with archetypes to explore the other question central to the book: Does power, as the oft-quoted British historian John Dalberg-Acton asserts, inevitably corrupt? Religion, politics and economic themes are embodied by the main characters to explore this question of corruption. For Tunde, the journalist, his journey is about uncovering and pursuing the truth, no matter how unpopular or dangerous.

The book contains some graphic scenes of sexual violence, mutilation and humiliation that are disturbing on their own, but perhaps even more so once the reader realizes they are descriptions of what women the world over have historically experienced. The scene in which a gang of women rape a man is among its more difficult parts to read. Alderman asks readers to examine their own unconscious bias about gender; the book is a mirror of our world today, flipped, unflinchingly, on its head.

Alderman asks readers to examine their own unconscious bias about gender; the book is a mirror of our world today, flipped, unflinchingly, on its head.”

I liked this book, as did Margaret Atwood, who it turns out mentored the author and encouraged her to explore her ideas. What’s different in Alderman’s telling, compared to other dystopian worlds like The Handmaid’s Tale and Vox, is that something is being given to women, not taken away. As the story unfolds, there is a feeling of fierce uprising that I found powerful to read, even as I watched the characters and their world spiralling out of control toward the end.

Another literary device the author uses is the “book within a book”; the story is actually a manuscript, written 5,000 years after the power emerges in women and the world reorganizes into a matriarchy. The manuscript is written as historical fiction to imagine what the early days of the revolution might have looked like, as told by Neil and sent to his friend Naomi. I’ll admit I found this device underwhelming, although the correspondence between writer and reviewer at the end of the book delivers some real zingers. My favourite line is the very last one, where Naomi suggests gently, “Neil, I know this might be very distasteful to you, but have you considered publishing this book under a woman’s name?” I laughed out loud at how ridiculous this advice sounds in 2019.

Does absolute power corrupt absolutely? It would seem Alderman believes so. All of the archetypes she explores are taken to their extreme—Roxy is betrayed by her crime family (in one awful scene, her brother cuts out her skein and sews it into his own chest); Allie becomes Mother Eve, a religious cult figure with millions of devout followers who will do anything to control the world; and Margot manipulates the situation to the point of global political instability on the brink of war. In the end, it’s Tunde I’m rooting for, wanting him to get out alive and find happiness amidst all the chaos.

The Power feels relevant today as more women are finding their voices, coming together and supporting each other’s experience of moving through the world as female. It’s also a cautionary tale about what to do with our voices as they rise, as we are not immune to the lure of power and the corruption it can invite. Canadian MP Jody Wilson-Raybould and New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern recently demonstrated what it means to lead with integrity and courage. As the mother of two teenage daughters, I am grateful to them for modelling how to use their power for the collective good.

Michelle Larstone is a Smithers-based communications and community-engagement practitioner. She enjoys community choir, urban cycling and reading with friends.