A Decade Later: Missing Women and the Media

In 2006, before the media storm over the Robert Pickton case, before extensive coverage of northern BC’s Highway of Tears and long before the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Women and Girls, Concordia University professor Yasmin Jiwani co-authored a paper, Missing and Murdered Women: Reproducing Marginality in News Discourse, with University of British Columbia professor Mary Lynn Young. More than a decade later, Jiwani reflects on where the journey to shift prevailing media representation of women and girls has taken us.

By Yasmin Jiwani

Eleven years ago, the issue of the missing and murdered Indigenous women was just beginning to sound an alarm in the public sphere. The public’s exposure to it was kindled by a small number of determined journalists working in concert with families and friends of the missing women. Our aim in writing this article was motivated by similar concerns and sentiments; namely, that if more people were aware of this issue, and if policy makers were sensitized to it, public and governmental actions would follow. Our intent, then, was to make a discursive intervention in the realm of academia, public knowledge (through the media), and drawing the attention of policy-makers to the issue.

Today, we are witnessing an official inquiry whose mandate is to investigate the issue of missing and murdered Indigenous women. However, it is an inquiry that has been fraught with its own internal issues, its imposed and inherent limitations, and its contested credibility within the very nations who have demanded it.

Today, the academic literature on the missing and murdered Indigenous women is far more extensive and detailed, highlighting links between the issue here in Canada, and similar patterns of femicides in Mexico and elsewhere. This is a pattern, as Melissa Wright rightly describes it, predicated on a discourse of disposability. Indigenous women are disposable bodies; their absence is unmarked, sparking some recognition but very little restraint from the perpetrators that use and abuse them.

Indigenous women are still being murdered. Public attention hasn’t put an end to these murders. Since 2006, we have witnessed the numbers increasing as more and more women are reported as missing and murdered with the RCMP’s 2014 report citing 1,017 women murdered and 164 who are missing, many of whom are Indigenous. That these numbers may be due to more families coming forward is only part of the explanation. The other part is the epidemic nature of these femicides: the killing of women because they are women and, more specifically, Indigenous women.

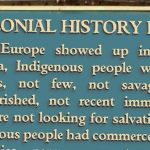

What also hasn’t changed is the colonial logic that is at play here. This logic is premised on the mythology of the “vanishing Indian”—the idea that Indigenous peoples would disappear as a result of disease, conquest and white superior military power and prowess. This colonial logic is still at work and apparent in the numerous stories that are published daily about Indigenous women as being unfit mothers, with statistics that demonstrate their ill health, addictions and an inability to survive, if not thrive, in the larger society.

This is the meta-discourse—an organizing way of encapsulating representations of Indigenous women. Such a framework then explains away the “missing” women by attributing their absence to their own actions—living at no fixed address, moving from one place to another and as lacking any sense of responsibility. For women who are murdered, the logic works to make them accountable for having been in the wrong place at the wrong time, and exhibiting the wrong kinds of behaviours. Women are then made culpable for the fate they experience. Such a move effectively shifts the blame away from the very institutions and structures of power that make Indigenous women vulnerable to structural, physical and emotional violence.

To neutralize the logic, we need to change society’s valuations of Indigenous women. This requires a concerted effort at all levels of the social order—from the way we think and talk about Indigenous women’s lives, to the structural conditions in which they are situated and the social conditions under which they are forced to live. To do this, we need to confront the legacies of settler colonialism that continue to shape and texture the lives of Indigenous people.

Yasmin Jiwani is a full professor in the Department of Communication Studies at Concordia University. She is also the Concordia Research Chair on Intersectionality, Violence and Resistance. She has published several books and numerous articles on race, gender, violence and media representations.