Connecting Research with People and Place

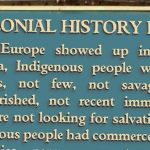

Photo courtesy Rick Budhwa

By Rick Budhwa and Tyler McCreary

It’s still fairly recent, and relatively uncommon, for researchers examining culture to do so through the eyes of those they study. However, this is changing; increasingly, researchers trained in the Western tradition seek to articulate and respect indigenous sense of place in their work by recognizing indigenous ways of knowing and being — not simply as part of the research data, but as frameworks informing research activity.

In their case study of indigenous-academic collaboration in northwest British Columbia, Rick Budhwa and Tyler McCreary demonstrate how research in indigenous communities can highlight the shortcomings of existing paradigms and contribute to the development of alternative approaches. Archaeological sites represent only a portion of the cultural resources derived from indigenous lands. Cultural resource management practitioners must also attempt to gauge the impacts of proposed developments on indigenous sense of place.

The prevalent archaeological lens for cultural resource management research focuses on material aspects, displacing understanding of the broader, often-intangible environment in which those resources exist. There is value in simply being on the land and better understanding traditional governance. Through indigenous-academic research collaborations, the importance of listening and spending time on the land is recognized as a means to advance research paradigms that recognize depth of place.

Budhwa began his career working as an archaeologist/anthropologist for the Office of the Wet’suwet’en in northern BC. “Although I emerged from school with an appreciation for the environment, I lacked a serious and profound connection to the land,” Budhwa recalls. He remembers being mandated, on random sunny days, to go out on the territories, without agenda. Just to be on the land. He recounts the first time when, fresh from university, his manager told him they would do exactly that.

The “territories” were referred to often. That’s how we referred to the land base. I interpreted his request as, “We’re going into the field.” So, I got ready for the field. I went to the office, got maps, got a GPS, got tools for the field, got my caulk boots, my vest, my compass, everything — I was ready for the field.

When I came down to the 12-passenger van, all the chiefs and elders that were joining us that day were in their normal, everyday street clothes. Some had cowboy boots, but no one looked like me. I thought to myself, “This is not very conducive to good fieldwork” but I was confident in my field abilities. I arrogantly assumed I was even prepared to “care for” some of these folks in the field, if need be. How could someone 60 years old in cowboy boots be as ready for the elements as a 30-year-old in caulk boots?

Most of the ride out to the territory was spent laughing at me. The chiefs particularly liked the spikes on the bottom of my boots, and were curious if I was planning on spending time on the glacier. I was even asked if my field vest doubled as a life preserver. The teasing and humour, while at my expense, indicated the ways I was being integrated into the community.

Once on the land, Budhwa witnessed people walking with purpose; others just strolled; what they had in common was they were all just being. Existing on the territory. Building relationship to the land. The story underscores the importance of researchers spending time on indigenous territories and listening to the voices of indigenous peoples, with the ultimate goal of creating meaningful connection.

For the Wet’suwet’en and Gitxsan people in northwest BC, culture and knowledge are not simply about material items, but refer to the social and spiritual relations between animals, environments and humans. However, in Canada, development projects often equate cultural resource management with archaeology and its inherent focus on artifacts. Archaeology remains a discipline entangled with the legacies of the colonial research that informed its development. Governing archaeology practices divided indigenous peoples from their cultural, political and economic relationships to the environment, relegating their culture to a fragmented geography of villages, campsites, pit houses and caches. Thus, they often fail to register the full depth of indigenous sense of place.

It is important to recognize space as not just a container, but as a constitutive element in human experience. Cultural resource management practitioners have too frequently avoided this in favour of more empirical, quantifiable research. Losing sense of place impacts both individuals and communities; connection to the earth is paramount. Once cultural resource management consistently incorporates the inherent connection between culture and land into its research, the discipline will be meaningfully and effectively representing indigenous peoples.

This piece was adapted from the research article Reconciling Cultural Resource Management with Indigenous Geographies: The Importance of Connecting Research with People and Place. Find the original article here.

Tyler McCreary is an assistant professor in the Department of Geography at Florida State University. His research focuses on how Indigenous-settler negotiations shape the governance of northern resources, labour markets, and communities.

Rick Budhwa is the publisher of Culturally Modified and an applied anthropologist who has worked within the realm of cultural resources for nearly 25 years. Rick attended the University of Western Ontario where he received his BA in anthropology. Later, he completed a post-baccalaureate diploma in archaeology and master’s degree in anthropology/First Nations studies/archaeology at Simon Fraser University. He currently teaches Anthropology and First Nations Studies at Coast Mountain College and is the principal of Crossroads Cultural Resource Management. Rick has been formally adopted into the Gitdumden Clan of the Wet'suwet'en in the traditional territories where he lives with his wife and two boys.