Curation and the Coronavirus: Collecting Pandemic Artifacts (Q&A)

Photo courtesy of the Royal Alberta Museum

Pat Myers is the curator of Work, Life, and Industry at the Royal Alberta Museum in Edmonton, Alberta. The Museum has been collecting the objects that have been defining the COVID-19 pandemic throughout Albertan communities. Culturally Modified caught up with Pat to ask about the process of curating objects in a pandemic, and what it means to be living through a historical event.

Why did the Royal Alberta Museum decide to collect artifacts from the pandemic?

We knew that this pandemic would have a profound impact on the province, and wanted to begin collecting objects that would let the museum interpret that experience to audiences of the future. It’s called “rapid response collecting,” and is certainly different from usual museum practice that generally waits to see what objects have long term historical value. There was no question that these objects would have lasting historical value, and museums around the world began collecting them immediately.

For example, we have no objects in our collection that would help us interpret the 1918 influenza epidemic. So it’s really important to be on the ground, collecting objects, from this critical point in our history.

What sorts of artifacts have you been getting? Has it been mostly digital at this point, or do you have hard copies as well?

We collect mainly objects, not documents. Many of the objects we’ve collected are still in use — the owners have donated them to us, but we won’t physically have them until the pandemic is over and they’re no longer needed. We’re looking for things that can speak to individual response, community response, business response, government response, as well as items that speak to the experience of living with a pandemic. We have masks, of course, made by individuals and companies, and hand sanitizer bottles from Alberta distilleries and breweries that transitioned into producing sanitizer. These items speak both to response to the pandemic, and the experience of living with it. We have two hockey sticks that illustrate social distancing, “keep a hockey stick length apart”. One being used by a broadcaster. He taped his mic to the end of the stick so he could still interview people in the community. The second one that will be coming to us is from a Calgary comic who taped a razor to the end of his hockey stick and gave his father a haircut! We have caution tape that circled playgrounds and identified them as off limits during the quarantine phase of the pandemic. These are just some of the items we’ve acquired.

Are there any items that seem to be more common, or that seem to embody what living through this period has been like for the community?

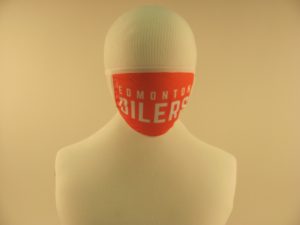

I think masks, certainly. They’ve now become a fashion accessory, and are really one of the iconic items from this experience.

A mask featuring the Edmonton Oilers. Courtesy of the Royal Alberta Museum.

A mask featuring the Edmonton Oilers. Courtesy of the Royal Alberta Museum.

Have you received any surprising or unexpected artifacts?

I wouldn’t say surprising or unexpected. We certainly have some delightful ones, such as the Stay at Home mug decorated with quarantine activities such as a blanket fort, books, and jigsaw puzzle pieces.

There was no question that these objects would have lasting historical value, and museums around the world began collecting them immediately.

How long does the museum plan on collecting pandemic-related artifacts?

I think we’ll be collecting for a long time. There are different phases to this experience. And as time goes on we will be able to reflect a bit, and have different conversations about what we want to add to the collection. I really want to think more about how we can collect around concepts such as community or hardship or conflict.

Alcohol-based sanitizer manufactured by an Albertan distillery. Photo courtesy of the Royal Alberta Museum.

Alcohol-based sanitizer manufactured by an Albertan distillery. Photo courtesy of the Royal Alberta Museum.

How long have you been working with the Royal Alberta Museum?

I’ve been with the museum for almost eight years. I moved over from another part of the department to join the project building our new museum.

What has it been like for you to attend to a historical collection, with the knowledge that you’re living through a historical time?

It’s a bit challenging, actually. Having to balance the seriousness of the situation with the happiness I get knowing I’m adding significant items to our permanent collection. And how grateful I feel when Albertans contact the museum and offer items for our pandemic collecting initiative. We’re getting a knitted COVID-19 bear (the bear has a doctor’s coat) from a woman in her 90s who knits bears as part of the program that gives them to children who are brought in emergency rooms, for example. She wanted to knit a bear as her response to the pandemic.

Are there any pandemic-artifacts that have provoked a particularly strong response for you?

A couple come to mind. And they’re very different. One is a metal sign used by crews working on outdoor projects such as water main repair. It has a large red stop sign shape in the middle and a hand in the “stop” formation. And it says — I’m paraphrasing — stay back two metres because of COVID. To have the name right on the sign makes it a product of this and only this crisis. And the second one appeared in my mailbox. Two children in my neighbourhood made little bracelets with colourful string and beads and put them in mailboxes as a surprise. They wanted to make people feel better. It certainly worked for me!

A do-it-yourself mask kit. Photo courtesy of the Royal Alberta Museum.

A do-it-yourself mask kit. Photo courtesy of the Royal Alberta Museum.

Does imagining how future generations might look back at this time change your perspective on a day-to-day basis?

It makes me want to collect as broadly as possible. To capture as many varied experiences as we can so there are lots of interpretive possibilities for curators of the future.

Is there anything you would like to add about the collection or about your experience collecting artifacts for it?

I try to remember that there are many different experiences, and to be sensitive to that. And try to collect representative examples of those experiences so not only one or two kinds make it into the historical record. I think that’s one reason we’ll be collecting for a while yet. We’ll be able to pause and say okay, what’s missing? What haven’t we thought about?

Pat Myers is the Curator of Work, Life, and Industry at the Royal Alberta Museum in Edmonton, Alberta. She has previously held positions working with historic sites in the province, and in heritage resource management. She has written a history of aviation in Alberta, and was a contributor to the province’s centennial history volumes.