Decolonizing BC’s Roadside History

By Joanne Hammond

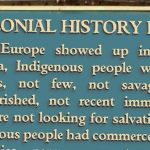

In September 2016, a sign was unveiled just up the street from my home in Kamloops. It’s the kind of familiar sign that dots Canada’s highways, meant for motorists to pull over, learn a thing or two about local history, and move on with new appreciation for the landscape. The new sign kicked off a campaign by the BC Ministry of Transportation to expand the province’s stock of public history and to invite suggestions about the stories people would like to tell.

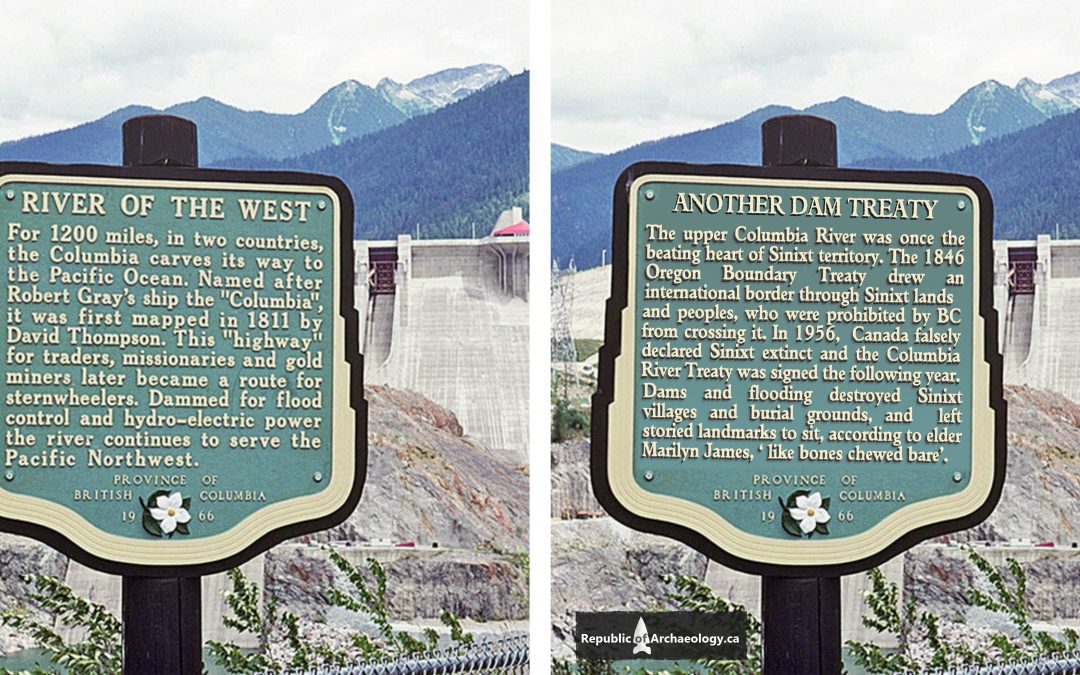

This particular sign overlooks a cultural landscape filled with indigenous heritage, blanketed with sites left by millennia of Secwepemc occupation. History that’s crucial to the place that would become Kamloops and the province that would become British Columbia. But on the new sign, all that indigenous history remains silent, left out of a narrative meant to convey a different past. Instead, it told a tired old story: white people came here, conquered wilderness, and now here we are, prosperous masters of the domain. These signs — and much public history in colonized places — have a job to do, and it’s not an honest one.

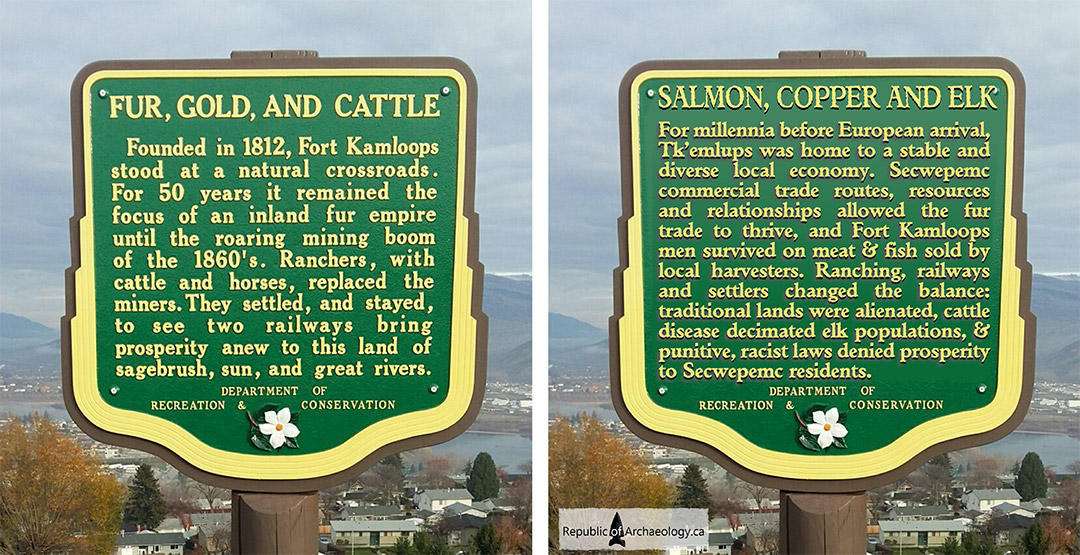

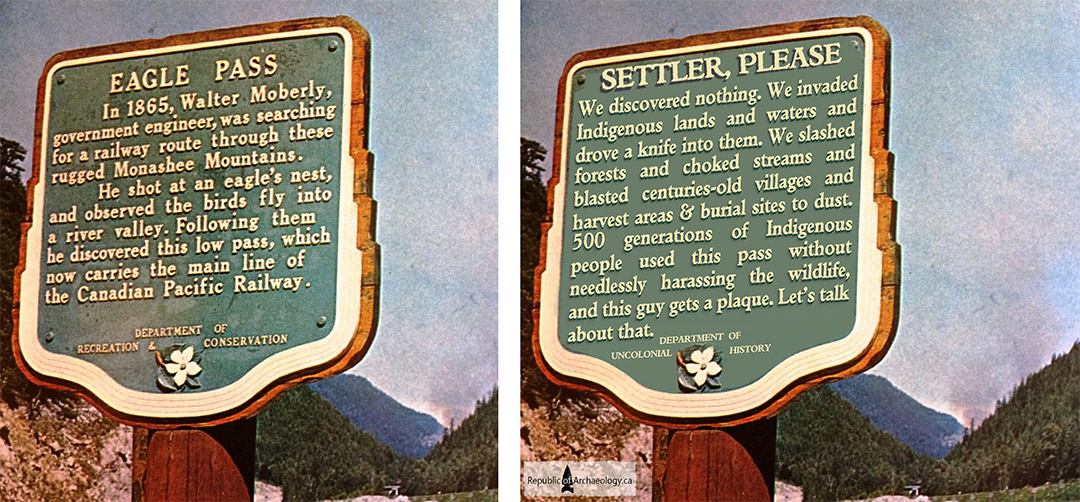

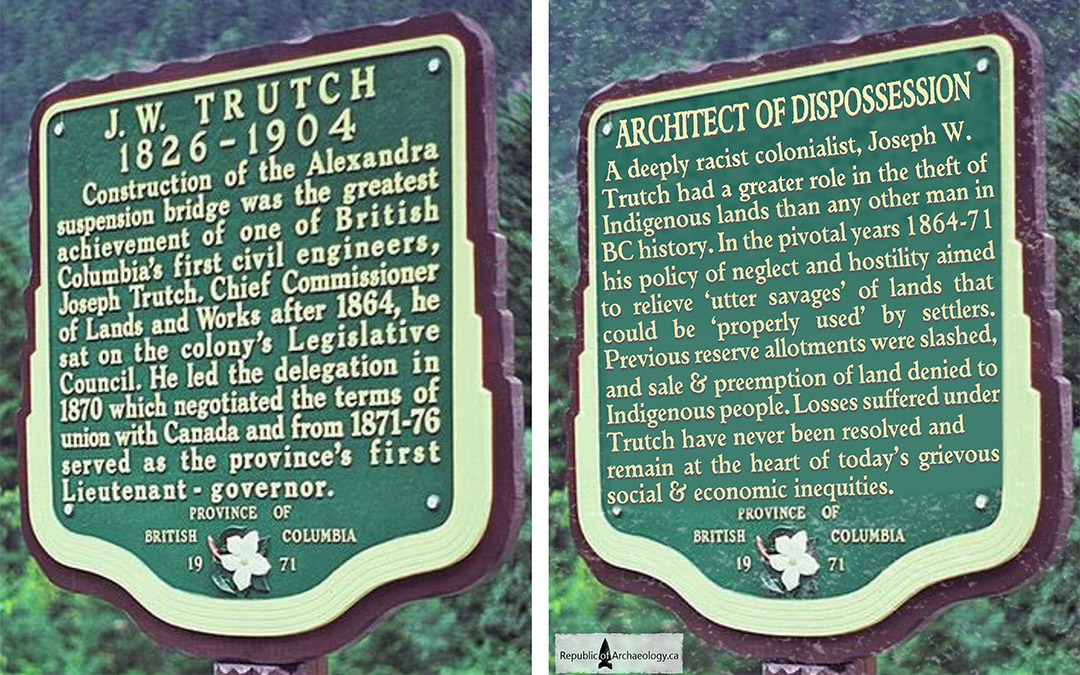

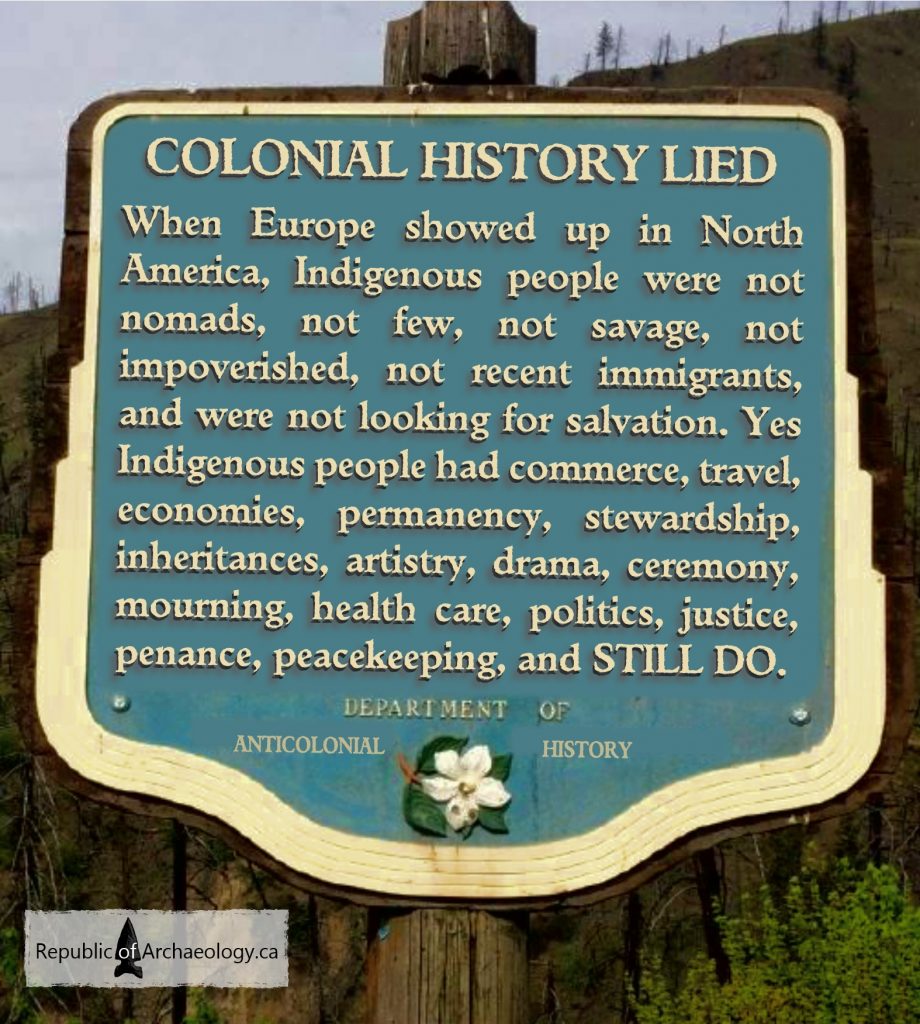

So, I got to work and began to rewrite BC’s stop-of-interest signs, digitally redesigning them and releasing them to the public through social and conventional media (#rewriteBC on Twitter, as well as stories on CBC, Metro, BuzzFeed and other news outlets). My goal was simple: awareness. Being a responsible witness to the past. To push back the veil of words to show alternate stories, to encourage people to see the holes in public history and to know that we can fill them with the truth.

Why does it matter? They’re just signs, right? What is to be gained from bearing false witness to history, as these signs do? What’s to be lost by telling the truth? A wise Anishinaabe I know answered this question bluntly: “A nation.” That’s no small risk.

Heroic, wealth-generating, no-harm-done-here narratives are the heart of public histories in colonial settings, and indigenous people are all but invisible. It’s not a mistake: the sparseness and insignificance of indigenous use, governance, occupation and enjoyment of these lands and waters is fundamental to the settler narrative of pioneering success. Canada’s very right to be is embedded in these lies.

Public histories that paint Canada’s story as inevitable, necessary and beneficent are dangerous <i>because they work</i> — and not just in the past. They actively maintain discriminatory structures of settler colonialism by rationalizing unjust historical acts and, in turn, rationalize contemporary marginalization of indigenous people. Think about this: when the history you read tells how it took white men to produce wealth from otherwise barren and ownerless land, how does that make you think about the people who claim title to that land? When they’re nearly invisible in every story your government tells you? When their only appearance is to help keep a white guy alive so he can fulfill his manifest destiny of farming some rocky bit of the Wild West? Stories of perpetual progress and righteousness have been so effective, they’ve fostered widespread incredulity about the antiquity and intensity of indigenous pasts — and subsequent colonial damages. They work against justice and reconciliation, by convincing us there’s nothing to reconcile.

Response to my rewriting project has been overwhelmingly positive. I’ve received much support and love from indigenous people, teachers, media, academics — even politicians. People who’ve lived with these signs in their communities are happy to see them revisited, have reached out to offer thanks and encouragement.

And government? Those in charge of the history? Less ebullient. Todd Stone, Liberal MLA and then-head of the ministry that runs the Stop of Interest program, told media at the time that he saw nothing wrong with the re-vamped Kamloops sign. But even Stone pays attention to the public current, and did acknowledge that more history inclusive of First Nations is needed. I am heartened by the broad public recognition that the time has come to do history more justly, more openly and more critically. I think that’s where change will come from.

I return to my wise friend’s take and ask, what’s to be gained by witnessing the past justly, openly, truthfully? The answer is the same: a nation. One we want, one that serves us all, one that recognizes the historical and ongoing role and value of indigenous peoples and lands.

We can’t choose the history that made this province; it’s got a lot of ugly bits that we can’t undo. But heritage is different. We can choose what we want to bring forward with us as our shared heritage. We can tell stories fairly, to try to balance the legacy of colonialism. Public history is a big responsibility, because it changes the way we think about each other. We can be better witnesses to the past, in the service of our shared future.

All images courtesy Joanne Hammond.

Joanne Hammond is an archaeologist and anthropologist in BC, where she lives and works in the unceded territories of the Secwepemc, Syilx and Nlaka’pamux nations. She serves on the Kamloops Heritage Commission and is a program advisor with Simon Fraser University's graduate professional program in heritage management. Joanne is active in outreach with schools, museums, community groups, professional organizations and governments to educate learners of all ages about Indigenous archaeological heritage and the history of Indigenous peoples and the Canadian state. She believes that we can craft socially responsible and morally defensible approaches to heritage research and interpretation that can produce outstanding human stories. Joanne’s on the web at republicofarchaeology.ca and on Twitter @KamloopsArchaeo.