What my Oma Taught Me About Strength (WITH AUDIO)

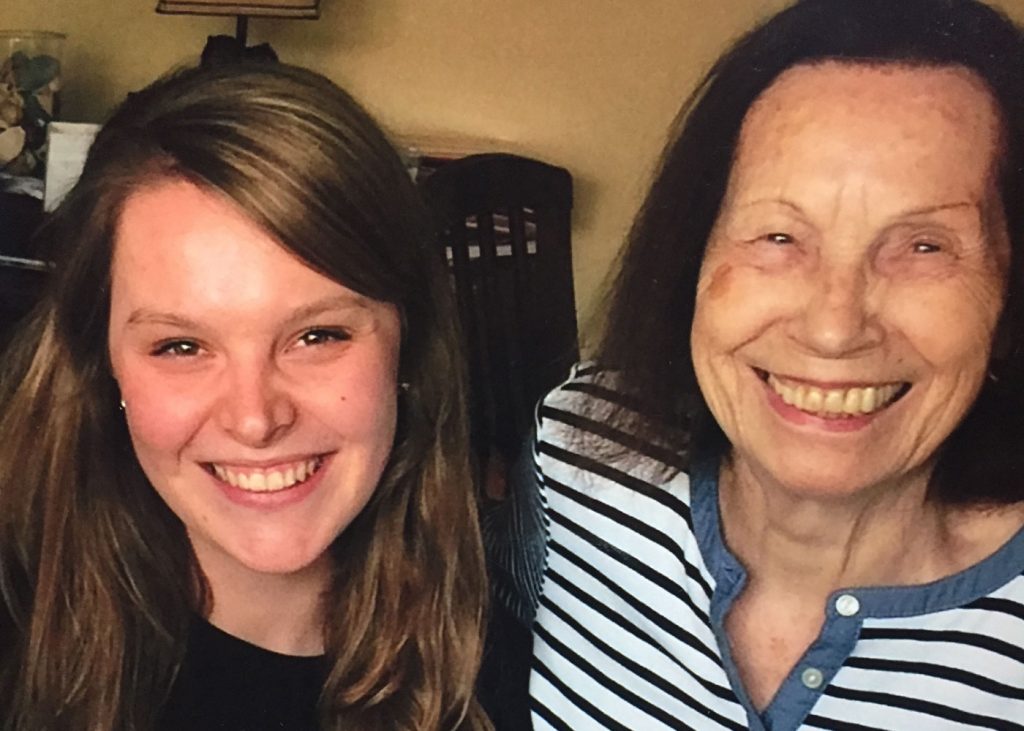

The author’s Oma, Anni, at age 18. Photo submitted by Elli Wills.

By Elli Wills

In a modest three-room home in the town of Kula, dinner has just ended and a multi-generational family of seven settles in for the night. Outside, the winter air freezes the ground, but the family gathers around their strong clay hearth, that great source of heat and togetherness.

Michael sits down next to his wife, Francisca, and rubs his hands together.

“Warm house, warm meal—another day done,” he says.

Michael’s two younger daughters, Anni and Julianna, giggle to one another. With a stern voice but a playful twinkle in her eye, their grandmother, also named Julianna, reprimands them while Margareta, the eldest sister, watches with a smile at the corner of her lips. After a while, the girls’ grandfather, Anton, declares it time to get some rest. Tomorrow is another long day.

This is the scene I imagine playing out as my 91-year-old grandmother tells me about growing up in the 1930s in Eastern Europe. My grandmother, Anni, whom I call Oma (German for “grandmother”), has lived a life of hard work, selflessness, determination and love. She has always been an inspiration to me, but now, at age 23, I find myself wanting to know more about her past. About how she became the strong woman she is today.

After graduating college in 2018, I moved back home. I live with my 18-year-old brother, 50-year-old parents and my Oma. We are each other’s biggest support system, yet we also experience squabbles, tensions and power struggles.

Since coming home I have often contemplated my family’s power dynamics, which spurred my interest in the power dynamics of my Oma’s family nearly a century earlier. She had a drastically different upbringing than my brother and I did, and my parents before us. Yet my current family structure also bears some similarities to hers. In order to further illuminate this perceived Venn diagram, I spoke in-depth with my Oma to learn more about her life.

As a preface, I knew that interviewing my Oma would be somewhat challenging. Though she speaks English well and her mind is still sharp for her age, the language and generation gaps are still apparent and made sifting through our conversations a little difficult. I considered the task a healthy challenge—one that encourages growth. Not to mention, I value every moment I have with her.

The author and her Oma in a recent photo. Photo submitted by Elli Wills.

My Oma learned discipline and sacrifice very early, helping her family as much as she could, even at a young age. At 16, she lost her father to the Second World War and at 63 lost her husband to a heart attack. She travelled alone when immigrating to America at age 30 and didn’t lose an ounce of the discipline she learned growing up when she began her life here. She is the strongest woman I know. Her story—however small a portion of it I was able to glean from just three extended conversations—deserves to be told.

Born in 1928 in an eastern European town called Kula, my Oma grew up living with her parents, grandparents and two older sisters. Kula was located in Bačka, a region of what is now Serbia. The terrain was flat and cultivated for grain. The rich lived closest to the town centre, with households becoming poorer toward the periphery. The church, school and pharmacy were all within several yards of each other. There was a man whose sole job was to ring a bell to alert cows that it was time to be done grazing. Compared to the 21st-century American suburbia in which I was raised and currently reside, Kula is a world apart.

According to my Oma, nights of talk and laughter around the stove in the wintertime were common and cherished. But for every peaceful night, there was a long day of toiling before it: My Oma’s parents, Michael and Francisca, worked from dawn to dusk in the wheat fields of the wealthy during the summer and in a hemp factory during the winter; after school, the three girls helped the grandparents around the house, going to work for other families when they came of age. Each played a role in the family’s survival.

Audio: “In the winter, we were sitting around the stove…”

Although my Oma’s family was not impoverished (“We all had a living, we never were starving!”), they would probably be considered low or lower-middle class by today’s standards, seeing that they provided labour to more affluent families in return for money and a portion of the harvest. This family unit operated in an environment of practicality and frugality, which in turn affected the household power dynamics.

When I ask my Oma who had the most power in her family of seven, she tells me that it was her grandmother: “Who had the power? Of course my parents did, but in the house it was my grandmother who had the power because she took care of everything and we children had to do chores.”

Audio: “Who had the power? Of course, my parents…”

My Oma’s parents transferred the day-to-day power to my Oma’s grandmother, Julianna, while they laboured in the fields or the factories. In my household today, my parents jointly hold the most power. They make decisions together, they handle the finances together, and they each contribute to the physical maintenance and emotional well-being of our household. Though they both have full-time schedules (my father as a high school teacher and my mother as a stay-at-home mom), there is no circumstance that compels them to delegate the highest power to someone else.

One could say, then, that Michael and Francisca had the highest authority because it was their household, but Julianna had the most “real-time” power because she, in essence, ran it. In fact, my Oma tells me that her grandmother was the person who spent the most time raising her. While Michael and Francisca worked nearly 12-hour days, Julianna saw to the child rearing.

“She was a good woman, but she was a tough lady,” my Oma notes. “Work was work. She had a lot of responsibilities.”

When Margareta, the eldest sister, married, moved out of the house and had children, a large portion of those responsibilities were transferred to my Oma. Namely, in the form of babysitting.

On the weekends, Margareta and her husband, Jacob, worked for a well-to-do family. Jacob did manual labour while Margareta walked a mile and a half to the fresh market at the centre of town to sell milk, butter and cheese. Meanwhile, Julianna (often called Julie), the middle sister, although not of age to be a maid, was a helping hand for a wealthy woman in town who made wine. The elder Julianna, my Oma’s grandmother, moved slowly and with a cane and therefore could not be responsible for an infant and a toddler, let alone make the trek to the market. The only free, able body left to watch Margareta and Jacob’s children was little Anni. She was 10.

“I had no choice,” my Oma says when I ask about taking on so much responsibility at a young age. “Not that I didn’t like it, but I was afraid to watch a one-year-old and a three-year-old.”

Audio: “I have to do it. My parents want to help them…”

Imagining myself in the same position is quite difficult; I used to watch my brother before he was old enough to be home alone, but I was a teenager at the time and our age gap was smaller than that of my Oma and her sister’s children. Moreover, if I ever had to babysit my brother, it was because my parents were taking a break from work to run errands or spend the night out, not because they were earning money.

My Oma describes a typical weekend day as such: “Margareta left for the market at 8:30 in the morning. She was gone a long time because she wanted to stay there to sell all her goods. I would look at the clock—10, 10:30, 11 o’clock. And then finally, after 12, I was relieved to see her coming down the street. It was a big responsibility for me at that age. And that was our life, to help each other. That was the way. My parents knew that I was too young to watch my sister’s kids, but that was our life.”

The family’s financial situation dictated their way of life in a way that my family’s financial situation does not. While it’s safe to say that my family’s wellbeing is also dictated by finances—we wouldn’t have a house, two cars, meals on the table and a handful of luxuries if we didn’t have a steady income—we still have more freedom than my Oma’s family did. Giving a 10-year-old the task of caring for very small children for hours at a time was just one distinct reflection of their circumstances. There simply wasn’t as much opportunity for middle- and lower-class families at that time.

And yet, though her family was sometimes stretched quite thin, my Oma remembers her father saying, simply, “I do what I can to help my family.” This mentality permeated the entire family unit, creating a sort of power from within. It was this core strength that kept the family grounded and saw them through it all. There was little room for argument or holding grudges. There were mouths to feed, expenses to be paid and life to be lived. For the sake of survival, sticking together was the only option.

“We were close together,” my Oma says of her family. “The closeness brought us so far.”

Audio: “My parents, we were talking and sitting…”

And because of the strong values that took root in their hearts, this family knew love. Kindness was not lauded as a mechanism for recognition but as something that you show to others because it’s the most basic and truest thing you can do for them.

“You know what my mom always did?” my Oma asks me. “She sewed button-down shirts for my dad. She sewed them all by herself.”

You know what my mom always did?” my Oma asks me. “She sewed button-down shirts for my dad. She sewed them all by herself.”

After digging deeper into my Oma’s childhood, I find stronger similarities than differences in our families’ power dynamics. To be sure, the differences are real. I did not experience the same socio-economic structure, political climate or geographical features that my Oma did in 1930s Europe. My early years were not spent living under the same roof as my grandparents. I did not, as a child, have to care for other children and grow up quickly as a result.

But I do know the concept of avoiding petty arguments for the sake of my family’s well-being. I see the good that comes when values like hard work, selflessness and togetherness take root in people’s hearts. I see in my family the same prioritization of family itself.

Perhaps the most powerful aspect of a family’s power dynamic is not the influence of external factors or even who claims the most authority in a household. Perhaps it is the ability to find strength within oneself and in each other.

Elli Wills is an artist and one of her favourite mediums is writing. In college she wrote for the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (UIUC) chapter of Her Campus Media, the leading online magazine dedicated to, written by and focused on empowering college women. She was also published in Montage, the UIUC undergraduate literary arts journal. As a recent graduate, Elli completed an internship at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, where she worked with the museum’s social media manager to produce, promote and analyze content. Before the end of the internship she had the distinct pleasure of interviewing a fellow intern for the museum’s Intern Spotlight blog series. A Chicagoland native, Elli aims to explore the world through writing, illuminating the unique stories of nature, art and people along the way.