The Politics of Habits and Citizenship During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Photo by Mélissa Jeanty/Unsplash

By Bicram Rijal

Amid the ongoing COVID-19 crisis, I have been intrigued by how the pandemic has changed the practices of handwashing and personal hygiene from being largely mundane habits, to becoming the most essential bodily acts in everyday life. I have wondered about the implications of such a change in perception, which led me to the following questions: what are the intended and unintended consequences of the institutional responses to the pandemic, particularly with handwashing? In what ways are the global messages of handwashing and personal hygiene shaping the relationships between citizens and nations?

The pandemic is a complex reality

The ongoing pandemic is complex, with impacts across social, cultural, political and bodily spheres. The social and cultural implications consist of new forms of interactions, behaviours and sociality. The political implications across the world include new kinds of cooperation, competition and support and blame between countries. In the national context, however, the political implications mean new ways of relating between citizens and the state, and new civic duties.

Who envisions the message for handwashing? Whose knowledge does it include or exclude? Whose lives are imagined or erased from it?

Meanwhile, everyday bodily practices such as handwashing and other hygiene and sanitary habits have garnered new meanings and importance. During the crisis, these otherwise private actions have gained new social and political significance.

While fears of becoming ill are everywhere, whether or not people subscribe to government recommendations around cleanliness has not only meant the difference between health and infection, but it has also become the distinction between civic duty and civic disobedience. In other words, as much as these behaviours are of public health concern, they have also become a question of everyday politics and governance.

Meanings, methods and unintended consequences of handwashing information

“The importance of handwashing cannot be overemphasized,” Dr. Bonnie Henry, British Columbia’s Health Officer, said to the public during a media briefing on March 9, 2020. A few days prior to that, B.C.’s Minister of Health, Adrian Dix, had reiterated that information on handwashing “bears repeating again and a hundred more times.” Like the global spread of coronavirus, the messages for handwashing are also present everywhere: from government and agency websites and news briefings, to cities’ public signs and notices, and social media sites. The instantaneity of their circulation reveals both the interconnectedness and the speed that characterize our globalized lives in the 21st century.

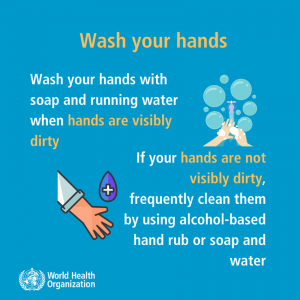

World Health Organization’s message for handwashing on Feb 02, 2020. Source: World Health Organization

However, the global circulation of handwashing information with a uniform and universal language, such as, “wash your hands with soap and water” demonstrates the limitations of demanding a change in behaviours without taking different contexts into account. According to the World Health Organization, one-third of the global population does not have access to safe drinking water. With that in mind, the uniform and universal handwashing message begs the following questions: who envisions the message for handwashing? Whose knowledge does it include or exclude? Whose lives are imagined or erased from it? A thoughtful engagement with these questions will help us understand how the handwashing information currently circulated is ethnocentric, limited and full of assumptions — such as the expectation that everyone has access to clean water, soap and hygiene products. What is certain about such a uniform message of handwashing is that it fails to consider the diversity of lived realities in different populations. For example, there is an ongoing water crisis among First Nations communities in Canada, and the Canadian government is often blamed for not fixing the problem. Media reports suggest that some communities have been under long-term boil water advisories and depend on contaminated water. The persistent water crisis among Indigenous communities is evidence of inequalities in access, and an irony in a country that has the world’s third-largest renewable freshwater supply.

A tanker delivers drinking water in a suburb of Kathmandu, Nepal in January 2016. Photo by the author.

A tanker delivers drinking water in a suburb of Kathmandu, Nepal in January 2016. Photo by the author.

In Nepal, my research in rural mountain communities demonstrates that water shortage is intricately connected to pertinent sanitation and hygiene problems. According to 2019 WHO/UNICEF joint progress report, only 27 per cent of the country’s total population has access to safely managed drinking water services. This is a stark contrast to Canada, where 99 percent of its population has access. Yet the two countries have circulated essentially the same handwashing messages pertaining to the COVID-19 pandemic.

These universalizing and homogenous approaches to COVID-19 prevention also prove that healthcare responses are not necessarily culturally sensitive. For example, when many communities in Nepal do not have access to handwashing facilities with running water, the illustration on a government-distributed poster of people washing their hands on a basin serves as a visual misrepresentation of everyday reality.

The current models of handwashing information have the unintended consequences of blaming the individuals, and giving a pass to structural inadequacies and inefficiencies. Whether it is in Nepal or in Canada, in the name of civic duties and responsibilities, the governments focus on individual actions and behaviors as a solution to a public health crisis, and refrain from attending to the systemic and structural problems of the healthcare system, including the provisions of clean drinking water and sanitation. This top-down, one-way travel of handwashing information from the governments carries a threatening message to the public: compliance and non-compliance to mandated health measures becomes a marker of who qualifies as a citizen, and who doesn’t. However apolitical the information may sound or seem, it is nevertheless political both in its delivery, and its embedded meanings and messages.

The ways in which the governments across the globe share the health and handwashing information reveal the political life of the pandemic. In Canada, for example, the overseeing health officers of respective provinces deliver the message to the public on the government’s behalf. The disseminated information on COVID-19 also urges the public to follow the recommendations by health officials. These practices may serve as a way of validating their point, asserting their authority and, what anthropologist Kim Clark calls, “standing apart from and above society.” The message is delivered as a health recommendation and primarily calls for the public’s voluntary action. However, at times these recommendations become warnings and enforcements.

Politics of citizenship

The governments’ handwashing information also embodies a message of “sanitary citizenship.” The outcome of this message, according to Charles L. Briggs and Clara Mantini-Briggs, is that those who buy into or neglect the government’s framing of the pandemic “as a problem that could be contained within simple and modernist narratives,” such as handwashing and hygiene, are then respectively divided into “sanitary citizens” and “unsanitary subjects.”

During the crisis, these otherwise private actions have gained new social and political significance.

But it isn’t just handwashing that divides people into these categories. Recommendations around physical and social distancing have also become measures on who can be considered a good citizen. On March 23, 2020, the Canadian Prime Minister, Justin Trudeau, addressed the nation calling for more civic responsibility from people. He said “enough is enough” to those who were yet to follow the public health advice of physical distancing. Highlighting the importance of social and physical distancing, Trudeau reminded, “If you choose to ignore that advice, if you choose to get together with people or go to crowded places, you’re not just putting yourself at risk, you’re putting others at risk too.” Then he made it clear that the government would draw on the approaches of both “educating people” and “enforcing the rules if that’s needed.” “Nothing that could help is off the table,” he said, before concluding, “listening is your duty and staying home is your way to serve.” Trudeau’s warning came right after some provinces and territories threatened to implement fines and arrests to enforce COVID-19 physical distancing measures. I read his warning as a reminder to the public of distinction between citizenship and non-citizenship, and between civic duty and civic disobedience.

However, the implications of health and hygiene practices are not just political — as a manifestation of citizenship — they’re also visceral, in the forms of infection and death rates caused by the virus.

As is evident in the United States and Canada, a simple act of wearing a mask has become a contentious issue. When government’s disease and infection experts and other officials speak different and sometimes opposing languages, it is likely for the public to get confused on what to do and not to do, whether that is in relation to wearing a mask in public places, or having outdoor gatherings, or reopening schools and businesses. In times of crisis, it is government’s onus to make the residents of its country feel comfortable and gain their trust in its policies and practices. However, that trust does not emerge automatically. I think that the clarity of understanding, such as having a clear distinction between physical distancing and social distancing, appropriate cultural assessment, such as being able to recognize how each community will be impacted differently by the virus and by recommendations, and fact-based communication, such as sharing facts in a way that the public is able to buy into them, are keys to a fight against the pandemic.

Cultural sensitivity seems to be pivotal in communicating the policies to the public in empathetic, patient and kind manners, instead of ruthless and homogenous ways. For the pandemic responses to get the positive results they aim for, the governments need to recognize diversities and complexities of communities and encourage rather than enforce the policies upon them.

During the pandemic, simple acts like handwashing and physical distancing have become ways in which citizenship is performed and practiced. The ways that these acts are recommended and enforced remind us that being a citizen is more than a legal document — it’s an ever-evolving relationship between the public and the government.