Indigenous Education through Homeschooling

By Carla Lewis

I had always planned to homeschool my eight-year-old son. Yet, when kindergarten rolled around, he decided he wanted to go to the local public school, where most of his friends were. The first morning went well. He was excited to take the bus and I followed him up to the school so he would know where to go and what to do when he got there.

It all went downhill from there.

After a few months in the classroom, my son’s self-esteem was at an all-time low from being bullied. He was showing a distaste for authority and lineups and bells. He said he hated “learning.”

He wasn’t the only one unhappy with the school system: I was having my own struggles as he came home questioning the discovery of our lands by Christopher Columbus and wore a colourful construction paper headdress, apparently meant to represent Indigenous culture, at the annual Christmas pageant. Rather than our own Witsuwit’en language, he was studying French.

We started our homeschooling journey after Levi, just five years old at the time, was beat up in the playground and then called a “tattletale” by his teacher. It took almost a year of being at home in a loving environment for both of us to shed the impacts of this system and begin to love learning in a more natural way. We have never looked back.

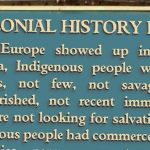

Since the early days of Indigenous children being taken from our homes and communities to attend residential schools, Canada’s colonial education system has taught Indigenous children to live in a way that is not our own.

While the last of these horrendous schools shut down in 1996, the public education system continues to deny offering Indigenous language education on an even playing field with English, and our history and cultures are rarely taught or appreciated. The result is yet another generation of our people who do not speak their language or know their own history, along with a nation-wide crisis of racism and ignorance against our people as many do not understand the unique political relationship that has shaped this country.

For generations, Indigenous nations have sought to rectify this, at least for our own people, by creating our own schools and fighting for control over curriculums and equality in the public-school system. While there have been excellent examples of success within the institutional setting, taking control of my child’s education by taking him out of the system altogether was the best choice for us.

Today, our “homeschool” is not a school at all, but rather a life-learning process where we both do our best to prepare ourselves for an uncertain future. We do not sit down and study formally for hours a day. We have deep conversations, we research the unknown questions, and we make every effort to connect and learn about our history, culture, language and land that was taken from us in past generations.

Most importantly, Levi gets to play, create and explore throughout most of his days and is growing up gaining hands-on learning within the traditional territory of our ancestors.

As a result of residential schools and the Sixties Scoop, I didn’t begin learning about my Indigenous identity until well into adulthood. My little boy, however, knows his nation, clan and house, knows how to participate in the feast system, knows our lands and many of our traditional skills and values. He loves hearing our drums, hearing stories of long ago, and he is proud of who he is.

We learn by actually doing these things rather than just reading about them.

We harvest our own salmon every season and we celebrate every fish he catches and the berries he brings home as he learns to be a provider for our family. We are supported by a group of other Indigenous families who choose to “lifeschool” their families in a similar fashion. Through this group of like-minded families, we come together and share skills and methods to be able to continue this form of education in an effort of decolonization.

Critics have commented on the socialization issues and lack of mainstream education standards for homeschooled children. However, Levi gets plenty of interaction with children through our daily lives and through sports. He has great relationships with our immediate and extended family and our clan and house members. In fact, building healthy relationships with self, others and our environment is the cornerstone of our education.

While we have never sat down and completed worksheets and workbooks, Levi has learned to read by reading. He has learned other formal subjects through hands-on learning like carpentry for math, science through experiments, and social and environmental issues through conversations. He is well above grade level in all subjects—aside from French.

Overall, he loves to learn again and is an inquisitive and thoughtful child.

Our way of living, our worldview, interestingly, is supported not just by our methods of education but an entire life change that is as much about economics as it is about education. Being able to homeschool my son as a single mom is only possible because, as a self-employed anthropologist and professional photographer, I am able to work from home. We live a sustainable lifestyle that isn’t based on consumption of goods, which keeps our monthly expenses to a minimum so that I don’t have to take on full-time employment outside the home. It requires the support of grandparents and extended family to work together as role models, educators and providers. It requires life goals that do not fit nicely within the status quo and we actively seek methods to learn and live and be well together.

It has its challenges to be sure, but as politicians continue to fight for control over Indigenous education, we have reclaimed that self-determination, at least in our own home.

Photos by Carla Lewis Photography

Carla Lewis is from the Gitdumden Clan of the Witsuwit'en Nation. She is an anthropologist, photographer and mother to her feisty eight-year-old son.