Why Life Speeds Up (and How to Slow Down)

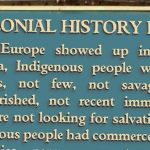

When you slow down, time slows down with you; photo by Joanne Campbell.

By Joanne Campbell

Does time pass more quickly for old people? And why do they drive so slowly?

I’m not old, but I’m older than I was. Clerks call me miss, a sure sign of their opinion of my advancing age and, if I had time to spend on such things, they’d soon hear my opinion of their opinion.

Despite my missness, I have a recently graduated teenaged daughter who, until recently, I drove to school via Babine Lake Road, a pastoral stretch of backroad in northwestern British Columbia. One early November morning, the air was crisp and the sky blue, so I brought my camera to take photos on the way home. A just-risen sun teased the frost out of the ground and I got some classic shots: horses in the mist, fields of golden grass, snow-topped mountains against a bluebird sky.

Very pretty, very picturesque. I was quite pleased with myself and my lovely photos.

A week later, on my morning return, the weather was not so beautiful and I thought, any fool can take pretty pictures on a pretty day, but on an ugly day like this? Curious and up for a challenge, I drove past my usual turn-off and carried on to the road’s high point overlooking the valley. I pulled over and stepped out. The earth was beige, the sky grey and dribbling rain. The world was dull and flat. No matter my frame, I couldn’t pull the ugly out of the day.

I was not pleased with myself and my insipid photos.

Defeated, I schlumped back into the car, put it in gear and started downhill. But instead of accelerating, I put my foot on the brake, just enough to keep the car rolling at walking speed. Window down, I looked, really looked, for something, anything beautiful. Out of habit, I turned on the radio, expecting to hear the usual CBC chatter but, instead, was surprised by the most angelic music: a simple violin lifted, a gentle piano flowed and as I looked over the valley, bathed in this achingly beautiful sound, time slowed enough for me to see what I needed to see. Textures, patterns and subtle colour combinations emerged from the gloom. Overwhelmed, I simply overflowed.

It was about time.

When I slowed down, time slowed down with me. The world relaxed and my heart opened. I could have gotten out and walked that stretch of road, but something about driving at walking speed was empowering, liberating. By rolling down the window of my box and opening myself to the world, I stepped into a moment. I broke a rule. The rule of time.

By rolling down the window of my box and opening myself to the world, I stepped into a moment. I broke a rule. The rule of time.

In some cultures, a clock is a tool, a schedule suggestion. In others, a clock is a whip and a schedule bible. In cultures where your wheels are king, time must not be wasted lingering on a highway.

Usually, I drive as fast as I’m able in order to minimize car time and stay out of other drivers’ way. I go a minimum of 10 km over the posted speed limit and, God forbid, never under.

These unsanctioned rules of the road are cultural rules, necessary for the orderly functioning of our highway transportation system. We aren’t allowed to willfully deviate from these rules, else we be subjected to some form of road rage for wasting someone’s time. There’s only so much of it to be had, so why spend it on ugly tasks like getting from point A to point B?

Einstein, the master of time, knew time wasn’t made up of points in a line. Thanks to his theory of relativity, we know time doesn’t flow or unfold; the whole of the past, present and future already exists, we just haven’t seen it yet. The physicist famously once said, “People like us, who believe in physics, know that the distinction between past, present and future is only a stubbornly persistent illusion.”

The past, once unfolded, doesn’t disappear. It exists as long as our memories do, as long as the material effects can last. The future? Well, that remains to be seen.

We can only perceive where we are in this moment and recall the past thanks to our human consciousness and fondness for photos and memorabilia, material goods and history: the evidence of geographical processes and other scientific methods of measuring events in time passed. Our perception of time is supposedly unique in the animal kingdom and its value to each of us is subjective, as evidenced by these seemingly contradictory views:

Determine never to be idle. No person will have occasion to complain of the want of time who never loses any. It is wonderful how much may be done, if we are always doing. ~ Thomas Jefferson

It is looking at things for a long time that ripens you and gives you a deeper meaning. ~ Vincent Van Gogh

The first sentiment gets a lot of quantitative stuff done, but it also sets us up for road rage. The second may not seem very productive unless you’re looking for epiphanies, a qualitative use of time. Ask any artist or musician or photographer: The muse only visits in the moment.

A photograph steals time, takes an infinitely small slice out of the non-linear continuum and seals it up in a flat-pack box, holds it frozen until its constituent atoms fritter away. Cameras are time machines that bring moments of the past into the present and ever into the future. Ironically, when you’re the photographer, your time spent behind the lens means you miss firsthand that which you are recording. You mentally disconnect from the now by preparing an image for later.

I didn’t take photos that transformative day because my camera wasn’t as enamoured of the moment as I, but I did go back when the light was better. I searched for those things I recalled were beautiful and I captured their image to augment the memory; they will remind me to slow down and step out of the box. The sense memory of that revelation will remain with me always.

So, does time pass more quickly for old people?

Einstein’s idea of time dilation for fast-moving objects states that time passes at different rates for observers travelling at different speeds. Exploring the metaphor, the busier you are, the slower time passes. Older people are less busy, with fewer new experiences. Young people run from experience to experience; even sitting still they’re learning new things. Young people move much more closely to the speed of light; time, for them, seems to pass more slowly. Old people move slowly, so, for them, time appears to speed up.

Young people move much more closely to the speed of light; time, for them, seems to pass more slowly. Old people move slowly, so, for them, time appears to speed up.

It’s all relative.

As an elder miss, I can tell you that being in the moment slows time right down, allowing us to do more of that ripening Van Gogh talked about and counteracting the speeding up that can engulf us. If slow time is for the young, it makes it the closest thing we have to an anti-aging time machine.

As for why the elderly drive so slowly, perhaps they’re just a bunch of out-of-the-box rule-breakers.

In years past, Joanne Campbell wrote fiction and fact for print and radio. Then, with a Master of Arts in Communication from Royal Roads University, she came to Smithers, B.C. and spent a decade as publisher of Northword Magazine. Now, she is an expeditor exploring her options. In the future, she will come back as a cultural anthropologist and explain why rich men try to catch the wildest of fish, only to let them go.