Empathy & Solidarity: Correspondence with a Bahraini Soul Sister

By Melissa Sawatsky

Prague, 2000

I first meet Bahiyah in Prague, where I’m living for a few months during my undergraduate degree.

She presides over a group of men and handful of women talking in accented English. Black hair cropped close to her head accentuating her dynamic features: large, almond-shaped eyes and full lips at the centre of a strong, square jaw line. When she speaks, the noise around her seems to dial down.

“Hey—where’re you from?”

“Uh, Canada—Vancouver. Just arrived this afternoon.”

She considers me for a moment.

“You up for a tour, Canadian?”

Past 3 a.m., the sky beginning to lighten, we emerge from the Karlovy Lázně nightclub and amble over Charles Bridge, listening to the Vltava River gurgle under our feet. We ascend the cobblestone lanes toward Petrin Hill in the haze of a new morning. She tells me of her childhood in Bahrain. She is justifiably angry about the media representation of Arabs and Middle Eastern countries, and she talks about how she struggles as an Arab woman in Europe trying to pursue an education.

I don’t know it then, but learning about Bahiyah’s experiences as an Arab woman and witnessing the balance of strength and sensitivity she possessed would become an education in cross-cultural understanding for this suburban Canadian.

Over the following weeks, we become surrogate sisters and promise to reunite in Egypt. We cannot know 9/11 is coming the following year. We don’t know it will be 10 years before we see each other again, with her homeland embroiled in revolution amidst the Arab Spring. But far from home in our early 20s, it seems as though we can walk from the border of the Czech Republic to the Giza Plateau and ride the Sphinx bareback into any country.

An Ocean Apart, 2011

Bahiyah sends me another email. This one has several links to graphic photos of casualties sustained by pro-democracy protesters in Bahrain. One man has had his head blown open during a clash with security forces under the command of the Al Khalifa monarchy. I suppress the urge to vomit and continue to open every link. I consider it my duty to witness.

Recently, our email exchanges are dominated by the events of the revolution in Bahrain, the subsequent security crackdown, and the arrival of Saudi troops and United Arab Emirates police. She apologizes for the graphic nature of the photos and videos she is forwarding to me, but insists: “The world needs to know. It’s a massacre.”

After our summer in Prague, Bahiyah and I keep in touch, updating each other on our respective lives and loves, as well as discussing our shared politics. She is living in the UK, but nonetheless involved in the National Democratic Action Society, Bahrain’s largest leftist political party.

When the uprising in Bahrain begins, in concert with several other countries in the Middle East following the ousting of dictators in Egypt and Tunisia, Bahiyah is inspired and hopeful. In early March 2011, she writes: “I’m so fortunate to be alive to witness what is yet to come—I’ve never been so proud to be Bahraini as I am today.” In response to the news that I will be visiting her in London, she adds: “Let’s hope Bahrain will be freed from its dictators by then.”

Bahiyah writes in early April that 20 masked men with machine guns showed up at her house to arrest her father.

Bahiyah writes in early April that 20 masked men with machine guns showed up at her house to arrest her father. He was released the next day, charged with four counts against the regime, and is to be prosecuted in martial court. Others have been killed while in custody and hundreds of people are being fired from their jobs.

Shortly after this, she sends me a link to an edition of Al Jazeera’s People & Power program called “Bahrain: Fighting for Change.” I get a sense of the hopes, fears and stakes under which the interviewed activists are operating.

Sayed Alwedaei, one of the injured activists, hypothesizes: “What will happen if this revolution doesn’t work? I think they’re going to target us one by one, one by one, whoever appeared on a camera. … Whoever spoke against them will be a target for them in the future.”

Alwadaei made it through Bahrain’s Arab Spring and is now the director of advocacy at Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy in London, England. In a 2017 opinion piece in The Guardian, he writes: “Five years ago, I fled Bahrain after being arrested, tortured and prosecuted for speaking to journalists during the Arab Spring. My campaigning work on human rights and democracy are anathema to the Bahraini authorities and I’ve been stripped of my citizenship and rendered stateless.” He also discusses the ongoing arrests and interrogations his family members have endured.

I cannot speak to the experience of living under an oppressive regime or in a conflict zone, having grown up in a relatively safe and quiet neighbourhood in Burnaby, British Columbia, but I witnessed some aspect of it through communication and information sharing with a friend for whom I care deeply. I listen to their voices and do what I can. I sign an Amnesty International petition advocating the rights of Bahraini activists. I act as a witness for Bahiyah. I write these words.

London, 2011

“Bahiyah! Over here.” She makes her way toward me. Do I embrace her?

I do. When we release, the glance that passes between us confirms we have been made strange. She wears her hair long now, pulled back into a ponytail, and her features are enhanced with makeup. The beautiful tomboy I remember from Prague is glamorous in London.

We lock eyes in short bursts, averting them from the realization that this isn’t a case of no time having passed between old friends. We will have to begin again.

We visit the Tate Modern, where she stands in front of me on the escalator, resting her hand on the railing. I struggle with the correct manner in which to address the recent upheaval in Bahrain.

“It must be hard to be here in London with everything you and your family are dealing with back home.”

“Yeah, part of me is still in Bahrain. Sorry I haven’t been better company.”

“Stop it. I want to be good company for you.”

On the main floor, in an exhibition of Photographs from the War in Afghanistan, we examine Simon Norfolk’s contemporary photos—group portraits of soldiers—displayed alongside those taken in the 19th century by John Burke.

“Notice how none of the soldiers look into the camera?”

I hadn’t noticed, and examine each of the historic John Burke photos in turn. She’s right—none of the subjects are looking into the camera.

“Is this a tradition for group portraits in Afghanistan, or something? A superstition?” I can’t believe I didn’t notice this detail—now it’s all I can see.

“I’m not sure, but it’s interesting, no? Like they’re acting, or protecting themselves.”

We meander into the Rothko room, and I mention one of my art history professors once told me that people have fallen to their knees weeping in front of his paintings. She considers this. Considers Rothko.

“Seriously? I don’t understand how these could make anyone cry.” I study her profile, steeled against all she has been made to witness. Her father’s arrest. Reports of torture and even death of those in custody.

When we reach the Surrealists, Bahiyah loses patience and walks ahead of me, but somewhere between de Chirico and Picasso we glance each other across the room with something that recalls what drew us together in our early 20s. Her eyes, steady on me. The corner of her mouth turning up.

Smithers, 2018

It’s been almost 20 years since I met Bahiyah in Prague, and the world is as chaotic and conflict-ridden as ever. The election of US President Donald Trump has resulted in the mobilization of unprecedented numbers of citizens and special interest groups across North America. I would never have imagined that in 2017 we would have to protest the abhorrence of white supremacy or advocate for the protection of numerous, hard-earned human rights and freedoms of the press.

Perhaps, for the majority of us, peace is an elusive and transitory state of being. I make small attempts toward living consciously on a day-to-day basis with meditation and yoga, and by reminding myself that the miraculous is so often disguised as mundane, but I don’t always succeed. The noise, nonsense and injustice of the world is a relentless interruption. My relationship with Bahiyah was unique in that we connected through that noise and chaos and found peace in the midst of it. Ours was an unexpected and uncommon correspondence.

I hadn’t heard from Bahiyah for a couple of years and thought perhaps our correspondence was complete when we reconnected on social media. My relationship with her continues to be one of the most transformative of my life. My desire to connect with her across time, distance and diverging cultural backgrounds—to remind her that my hand is outstretched in empathy and solidarity—is a small seed of peace I carry with me.

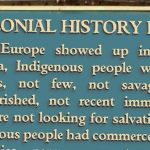

Prague, Czech Republic

Charles Bridge

Charles Bridge

Author visiting Bahiyah in London, 2011

Melissa Sawatsky is a writer currently living on unceded Witsuwit'en territory in Smithers, BC, where she works at the Smithers Public Library, as well as serving on the board of the Bulkley Valley Community Arts Council. She also facilitates creative writing workshops for young writers. Her work has appeared in Room Magazine, Northword, The Maynard, Poetry is Dead, Sad Mag and Rhubarb, among other publications and anthologies. She has an MFA in creative writing from the University of British Columbia.