How Stories form our View of the World

Photo by Tucker Good/Unsplash

By Michelle Vander Wal

The importance of a story to a child cannot be overstated.

More important, even, is the child’s own story. Children love to hear the story of their birth or adoption. They ask over and over again to be told how their family came to be and where they are from. Ritual, faith, implicit teaching all reinforce the story. The story is an anchor for children to imagine their future: Will I have the same job as my parent? Will I live in the same city, province or country? What will my world look like in the future? Where do I belong? What is my purpose?

Now take away that story. Children are left without a past or purpose, rudderless in their own present. They cannot cast a vision for future journeys for they have few or unstable reference points. The disenfranchised all struggle to make their stories make sense. They are searching for a worldview that can give them a solid place to stand in the world. Some find it in social justice, some in faith, some in family. Like a tree, children should have deep roots to the past and branches stretching for an infinite future.

Like a tree, children should have deep roots to the past and branches stretching for an infinite future.

Worldview is an underpinning concept of public education. It is explicit, using the singing of the national anthem to indoctrinate the concept of citizenship. It is implicit, as in arranging a classroom with work groups and circle space so that students can face each other, to begin the understanding of collaboration.

In a recent Grade 4-5 class I taught on early societies, we watched a TED-Ed video on ancient Sparta and that city-state’s style and purpose for education. It was quite different than what children in Canada encounter today. When asked to summarize the goal of Spartan education, my students came up with several comments. When asked to contrast this with the goals of Canadian education my students came up with few answers. We were left looking at each other, wondering what it was that Canada wanted them to be. Maybe the truth is, we don’t know.

Attending a workshop on Indigenous history and the residential school system led by Anishinaabe writer and educator Niigaanwewidam James Sinclair, I was struck by the story he told. Sadly, it is not a unique story. He framed his own place, his own worldview, in it so well but, shockingly to me, he also framed mine.

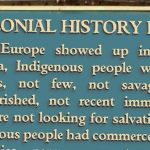

I was the student in the classroom being told a story about Canada that was not honest and complete. It had no depth or roots. It left huge gaps in information. What had happened to all those groups of people that were here during first contact?

It took me a few years to realize that those people existed on reservations and in other communities. It took a couple more years to understand that, for many, their lives were not like mine. I was given a worldview of Canada based on misinformation and social prejudice. I was given a worldview that would have eliminated whole cultures from Canada’s future. So I went hunting for Canada’s past in archaeology and then, delving even more deeply, for my own past in theology.

Building on those studies, I can see that Canada’s worldview is shortsighted. We are missing an anchor—our connection to place, our loci. We have suppressed spiritual intelligence in our society because we deem it private, not a topic of public conversation. We are beginning to see that our First Nations peoples have offered a more open way for us to connect our modern lives to this land, to our souls. Only now are we beginning to understand what Canada has lost and, perhaps, what can be regained.

The Canadian worldview has been ripped wide open in the last few years. The apologies given by Ottawa over residential schools, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Woman and Girls is telling a new story. How do we mesh this narrative with the one we parade in commercials and historical vignettes? How do we explain Canada’s dirty secrets to our students who are trusting the words of our national anthem—the true north, strong and free?

How do we mesh this narrative with the one we parade in commercials and historical vignettes? How do we explain Canada’s dirty secrets to our students who are trusting the words of our national anthem—the true north, strong and free?

We start by telling them the story, the whole story, the unvarnished truth about how our current Canada was born, grew and is maturing. We rediscover all the resources of this land, both economic and social, cultural and spiritual. Then we invite them to imagine a Canada where we do not keep reinforcing and glossing over the mistakes of the past. We can create a Canadian worldview by embracing all of our peoples, in the circle, face to face, as family. Then, as a country, we can all have deep roots and branches to the sky and beyond.

Further reading:

Education for Peace Curriculum

Moving Toward Reconciliation in Ontario’s Publicly Funded Schools

Aboriginal Perspectives: A Guide to the Teacher’s Toolkit (Province of Ontario)

Aboriginal Worldviews and Perspectives in the Classroom (BC Ministry of Education)

Michelle Vander Wal is an elementary school teacher in southwestern Ontario. After gaining a BA in North American archaeology, Michelle pursued a Master of Theological Studies in Early Christian History. Finding a teaching job that kept the same hours as her three children led her to complete a B.Ed. as a second career. Michelle enjoys teaching social studies in her classroom and educating a new generation of Canadians to appreciate a wide variety of cultures and ask critical questions about their world.